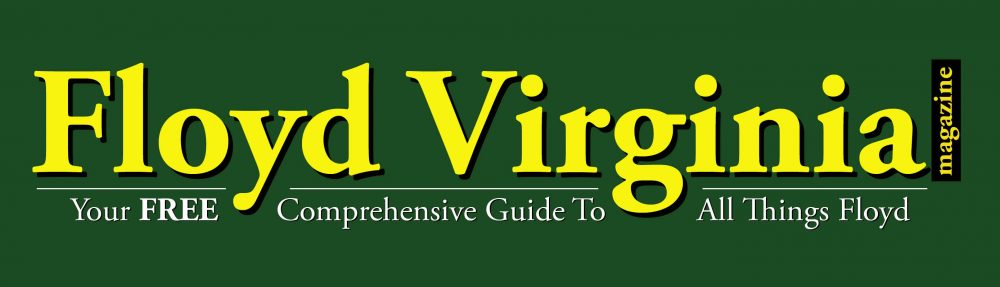

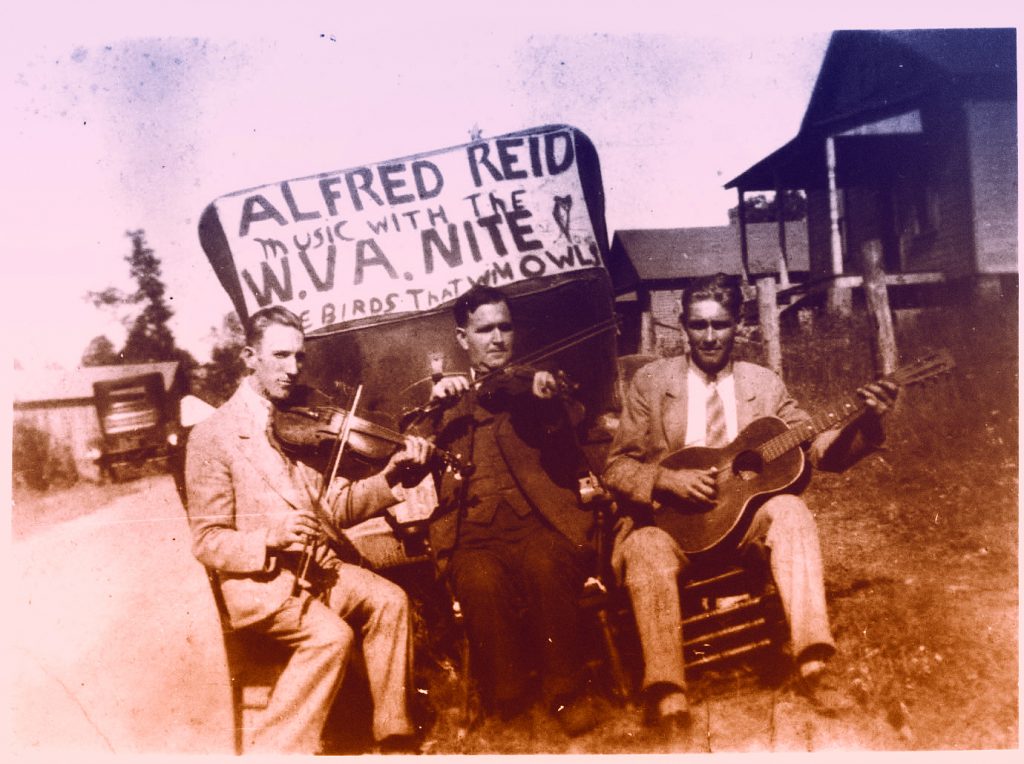

Alfred Reed and fellow musicians

Floyd County’s musical scene goes back to the mid 1700’s, with the arrival of its first settlers. Wherever people gathered, there was song, with or without accompaniment. Anyone or anything that could make a sound or keep a beat would play a role in making music.

At least a fiddle or banjo, some of which were homemade, could be found in many of the area’s early homes. Later, mail order catalogs offered harmonicas, autoharps, guitars, mandolins, and basses for all, while pianos and organs graced the homes of more prosperous citizens.

Floyd County is part of the Crooked Road Heritage Music Trail which recognizes the ties of the mountain music scene to the region and community. These musical traditions have been carried on by many groups and individuals, including folks coming together for front-porch gatherings, as well as shape-note singing performed in churches. It also includes widely-recognized musicians such as the Floyd County Ramblers, the Korn Kutters, the Conner Brothers, Randall Hylton, Upland Express, and Morgan Wade. Whether the music comes from humble homes and modest churches, or whether it’s played from stages with sold-out audiences, Floyd County’s music uplifts and sustains.

One of the early pioneers of the music scene receiving recognition along the Crooked Road is Alfred Lee Reed; sometimes spelled Reid. Like his older sister, Alfred was born in Floyd County to parents Riley and Charlotte Akers Reed. Riley Reed was a farm laborer in the Alum Ridge area, but eventually moved the family to West Virginia in search of employment.

One of the early pioneers of the music scene receiving recognition along the Crooked Road is Alfred Lee Reed; sometimes spelled Reid. Like his older sister, Alfred was born in Floyd County to parents Riley and Charlotte Akers Reed. Riley Reed was a farm laborer in the Alum Ridge area, but eventually moved the family to West Virginia in search of employment.

Also like his older sister, Alfred Reed was born blind. Born on June 15, 1880, Reed displayed an early gift for music. He obtained a fiddle at a young age, but because of his disability, he learned to play by ear. Alfred continued developing skills on his own, without the kind of formal training most children had in those days.

Then one day, Victor Talking Machine Company of New York executive, Ralph Peer, brought a field unit to the Bristol Tennessee/Virginia area to make recordings of the music of the mountains. At the July 1927 Bristol Sessions, Peer heard Reed playing his “The Wreck of the Virginian”; a song about a railroad disaster. This led Peer to invite Blind Alfred – so named by Peer – to perform four songs Reed had composed. Blind Alfred performed a solo rendition of “The Wreck of Virginian”, as well as three sacred songs: “I Mean to Live for Jesus”, “You Must Unload”, and “Walking in the Way with Jesus”. Alfred’s son, Arville accompanied his father on guitar.

The Bristol Sessions served to help preserve the music of the mountains and make it available to other parts of the country. Peer recorded not only Blind Alfred, but also a number of other acts, including Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family, who also made their first recordings at the 1927 Sessions.

The Bristol Sessions served to help preserve the music of the mountains and make it available to other parts of the country. Peer recorded not only Blind Alfred, but also a number of other acts, including Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family, who also made their first recordings at the 1927 Sessions.

Blind Alfred’s best recordings depicted the realities of life in rural America. His last recording in 1929 was probably his most famous song, “How Can a Poor Man Stand Such Times and Live?” That song was later recorded as a cover by Bruce Springsteen. After Springsteen, it was also recorded as part of a Ry Cooder tribute album to Blind Alfred.

Like much of the music from Blind Alfred’s time, his words spoke about life as he knew it. One of his songs, “Why Do You Bob Your Hair, Girls?”, was a protest of sorts against women’s hairstyles of the 1920s, as well as his own concern about women’s moral integrity.

Reed’s recording career was cut short by the Great Depression, as the cost of an album was a luxury beyond the reach of most rural Americans. He continued to perform, however, playing at dances. He also gave music lessons and sold printed copies of his own lyrics. He even played his fiddle in town with a cup alongside to provide for his family. Reed kept performing in public until 1937, when West Virginia adopted a statute banning blind street musicians.

Reed and his wife, Nettie Sheard, had six children, and he became an active Methodist lay minister in his later years. In the end, rumors suggest that he was literally a starving artist when he died on January 17, 1956, in Coal Ridge Hollow, West Virginia. According to Blind Alfred’s descendants, however, he was given great care by a close-knit family, and his last years were comfortable.

Reed’s music was revived by an increased interest in the Appalachian sound, as well as by the covers recorded by Springsteen, Cooder, and groups like the New Lost City Ramblers. Some of the interest that generated impetus for The Crooked Road came from songs by musicians like Blind Alfred Reed. Reed was inducted into the West Virginia Music Hall of Fame in 2007. In 2020, his song, “How Can a Poor Man Stand Such Times and Live?”, was added to the Grammy Hall of Fame.

Reed’s music was revived by an increased interest in the Appalachian sound, as well as by the covers recorded by Springsteen, Cooder, and groups like the New Lost City Ramblers. Some of the interest that generated impetus for The Crooked Road came from songs by musicians like Blind Alfred Reed. Reed was inducted into the West Virginia Music Hall of Fame in 2007. In 2020, his song, “How Can a Poor Man Stand Such Times and Live?”, was added to the Grammy Hall of Fame.

Blind Alfred Reed stood as one of the first in a long line of protest musicians. His disability made for rough times in a tough economic era. We owe a debt to those like Blind Alfred Reed who reflected the circumstances and feelings of mountain folk and who continue to keep alive the sounds of the mountains today.

The Crooked Road Heritage Music Trail

www.TheCrookedRoadVA.com

The Floyd County Historical Society

217 North Locust Street, Floyd, VA

www.FloydHistoricalSociety.org • 540-745-3247

info@FloydHistoricalSociety.org